Writing an Introduction

The introduction is the most important paragraph in your paper. A strong introduction is the first step to a strong paper. You can expect your reader to read your essay’s introduction more closely than any subsequent paragraph. In this unit, you will learn about what functions an introduction serves, how to make your introductions more effective, and some common tendencies to avoid.

“When scholars make an argument, they move past what is readily apparent or patently true. They do this by posing an analytical question, intervening in a debate, or explaining an important discrepancy in a text, issue, or topic.”

-HarvardWrites

Introductions in the wild

Consider the sample introduction to the right, adapted from Levitsky and Loxton (2013). Based on what you observe, what functions does this introduction perform? You may submit your thoughts below.

What does an introduction do?

Your introduction should do three things.

( 1 ) A strong introduction motivates the paper by telling the reader the the puzzle you will solve, the debate you will resolve, or the problem you will address.

( 2 ) It logically builds to the research question. It makes clear how that research question answers something about the puzzle you have identified, intervenes in a debate, or addresses a given problem.

( 3 ) It previews the argument. You should be able to state your argument in no more than 1-2 very carefully thought out sentences – a good statement of the argument here is precise, concise, and falsifiable. If it is causal, the statement of the argument should clearly identify your independent variable, dependent variable, and (often) your mechanism. You can read more about forming and stating falsifiable arguments here.

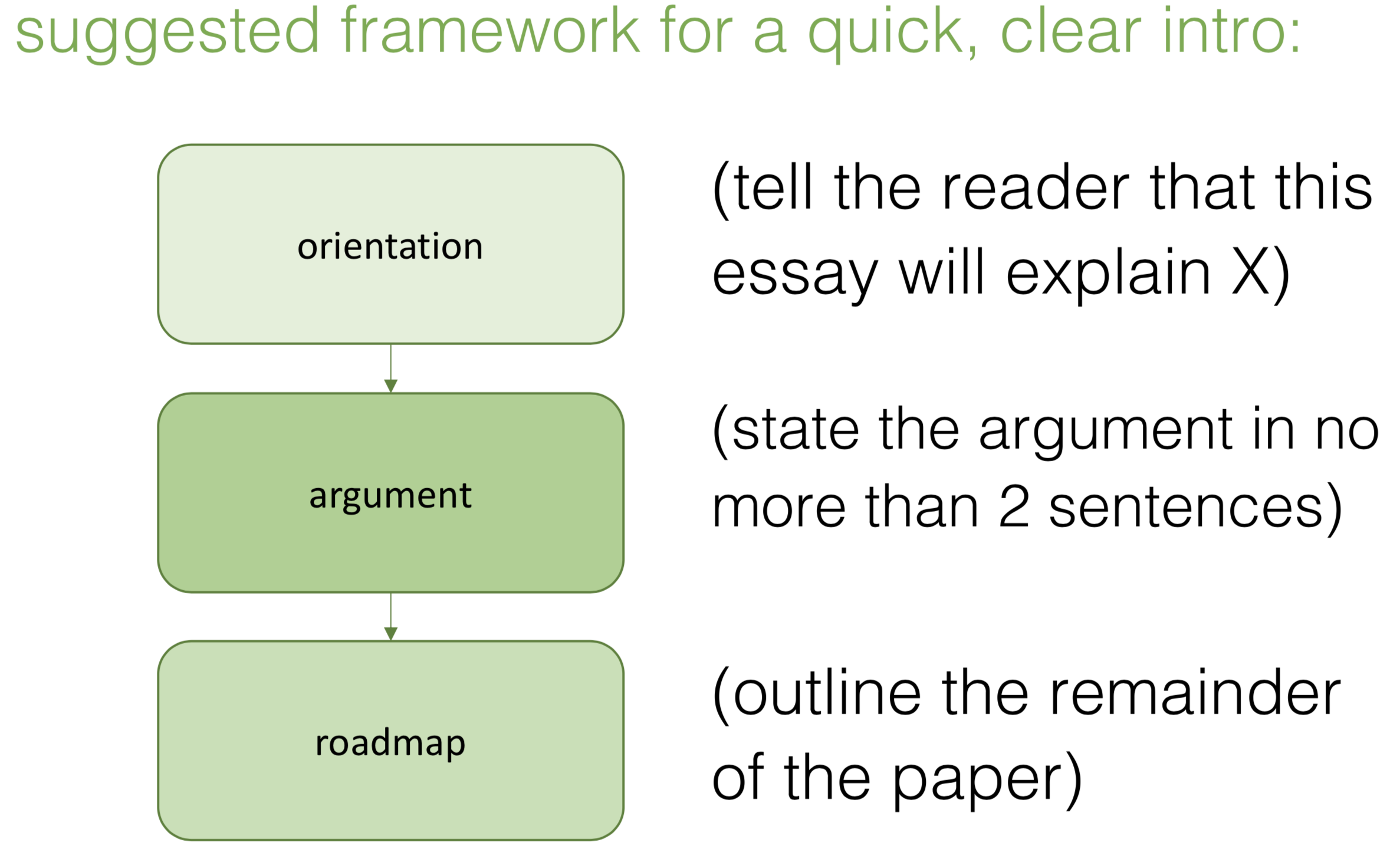

A framework for introductions

In the following video, we will walk through a basic framework for writing concise and effective introductions that successfully motivate their inquiry, identify their research question, and preview their argument. This framework can help you make choices about what material to include in your introduction and what should be moved elsewhere.

How to preview your paper

Many introductions go beyond previewing the argument and offer a roadmap the remainder of the paper. A good roadmap helps preview your main argument by clarifying how you will make it over the coming pages. It should describe the structure of your argument, the evidence you will use, and the goals your paper will accomplish. You can think of a roadmap as all of your subsection topic sentences consolidated into one brief piece of prose. Roadmaps should be brief and direct:

“The remainder of this paper does X, Y, and then Z”

“In this paper, I first X. I then use X to demonstrate Y. I then explore Z by doing W. Finally, I present evidence for Z by doing A, B, and C.”

“Section 1 does X. Section 2 does Y. Section 3 describes Z.”

While roadmaps are helpful for orienting your paper, do not get bogged down detailing your argument. A 10,000 word article published in an academic journal will often have an introduction that is only four or five sentences long. You should consider using 1-2 sentences to motivate your paper with a research question or puzzle, 1-3 sentences to state your argument, and 1-4 sentences to preview the reminder of the paper. While some forms of writing may allow more space for a richer introduction, you should use no more prose than is necessary to motivate, identify, and preview your argument.

Practice by revision

Read the introduction printed below (adapted from Caney 2005). Consider whether it fulfills the three elements above, and how you might improve it along those lines. Submit three possible improvements to the introduction using the form to the right.

How can I improve my introduction?

In the following video, we apply the ideas discussed above to work through a sample introduction and identify simple ways we can sharpen it.

What should I avoid?

Introductions in political science can be very different from introductions in adjacent disciplines like history or anthropology. In some disciplines, longer introductions are encouraged, and serve the purpose of guiding the reader slowly from a hook or setup to, eventually, the argument. In political science, we instead place our argument upfront, allowing the reader to reach it as soon as possible. In some disciplines, especially history, introductions serve an additional function beyond the three listed here - they present background, context, or color that helps create a sense of the setting in which the argument is being made. In political science, context is less important unless it is in direct service to understanding the argument. Furthermore, if an essay does include a deeper discussion of context, rather than in the introduction, we often place that discussion in a section of the essay body.

In addition, consider following these smaller tips:

You should avoid including anything in the introduction that is not serving a clear purpose. This especially includes unnecessary “windup” or “throat-clearing.”

Statements that a question or a phenomenon are “important” are usually not useful, and rarely falsifiable. Avoid “political scientists have always argued” or similar statements. Avoid relying on real-world impact to justify the importance of your research question. In political science, the primary reason that a research question is important or interesting is because it is poses a question that we cannot easily explain.

Tying it all together

How would you write an introduction for the following research question and argument? Outline what you would put for each part of the introduction.

Question: Why do some young democracies conduct free and fair elections, while others are still marred by vote-buying and election fraud?

Argument: I argue that young democracies are more likely to maintain free and fair elections when they face credible international oversight with observers on the ground at polling stations, because on-the-ground observers ensure transparency and that electoral irregularities are, in fact, observed.

How does this connect to what I learned in Expos?

Your Expos class focused on the elements of academic argumentation. When writing in political science, your thesis; your argument; and the question, problem, or what’s at stake are of key importance. These should be clear in your introductory paragraph.

Your thesis is your main insight or idea about the topic.

The argument is the series of ideas that the essay lays out which, taken together, support the essay’s thesis.

Questions, problems, and stakes motivate the paper, making it clear why someone might want to read an essay on that topic.

Here are some important things to keep in mind for how this all relates to political science introductions:

In political science introductions, focus less on coming up with just one concise sentence that explains your main idea (this can be more of a requirement in the humanities). Your thesis should be specific, but complex (causality is complex), and so it may require two sentences to fully lay out your independent variable, dependent variable, and mechanisms (as well as the conditions through which the causal process happens).

Think of the preview as laying out your argument. There are a series of sub-claims that are logically connected and developed that support your thesis. All of these, taken together, comprise the argument. How you develop and organize your sub-claims is crucial to the structure of your paper, so your preview in your political science introduction is a really great check on the overall logic of the paper.

Political science papers are motivated by problems (tensions or puzzles that lead to questions). Be sure to get to these stakes in your political science introduction relatively quickly; most of the material before your thesis statement and preview should be setting up the problem or puzzle that leads to the question that your thesis attempts to answer.